When we hiked back from our research glacier in November 2019 I, Walter, never imagined I would not visit the Himalaya for the next two years. Patient 0 developed symptoms in Wuhan on 1 December 2019 according to the official statistics and that was the start of it all. Lockdowns, boosters, vaccines, R-numbers, variants of concerns, quarantines, 2G and 3G policies were abracadabra to most of us back then. And look at us now. Nepal was also hit hard, in particular during early 2021, with a code black in the hospitals with many casualties as result.

COVID-19 also had a major impact on our science. We bravely motored though the lockdowns, wrote our papers and proposals, but not seeing each other and not being able to be in the mountains we study has an undeniable impact on mental wellbeing and creativity. It also impacts our work in a more direct way as we could not collect our data in the field and we had no idea of our stations measuring the mountain water cycle were still functioning.

By November 2021, the situation in Nepal had improved and we slowly accepted the idea that this would be a new reality for a long time to come. I decided to go to Nepal and together with Jakob Steiner, who did his PhD in my group and who works now at ICIMOD in Nepal, we went back to the Langtang valley for the first time in two years to take stock of our instruments.

COVID is not the only issue Nepal needs to deal with and an extreme monsoon season caused a big disaster in the town of Melamchi in June 2021. The saturated soils, persistent snow, extreme rain and high temperature conspired to generate a large debris flow which killed 5 people, destroyed hundreds of houses, and damaged bridges and roads. We tried to reconstruct the origin of this disaster and trekked through the Yangri Khola valley all the way to the source area of the debris flow.

This trip reaffirmed my believe that dealing with climate change induced extremes and cascading disasters is the ultimate challenge in the Himalaya. Limited research has been conducted into these compounding events and their controls and this will be one of our main aims of the coming years.

We continued to Langtang by crossing the Ganja La pass (5130) in a meter of snow, which was a challenge, in particular for the team of porters supporting our research. We arrived in Kyangjin, the highest village in the valley after a very big day. It felt like coming home and nothing had changed except that most lodges in the village had further expanded and build their lodges higher. This has been a local tragedy-of-the-commons that has been going on for years now. The biggest and highest lodge presumably gets most tourists, and all lodge owners are forced to expand on the expense of the charm of the village and with hardly any tourists visiting in the past years it hurts to witness this. However the hospitality of our hosts Gyalbu and his wife Lobsang is unmatched and so is their Dal Bhat and sea buckthorn juice.

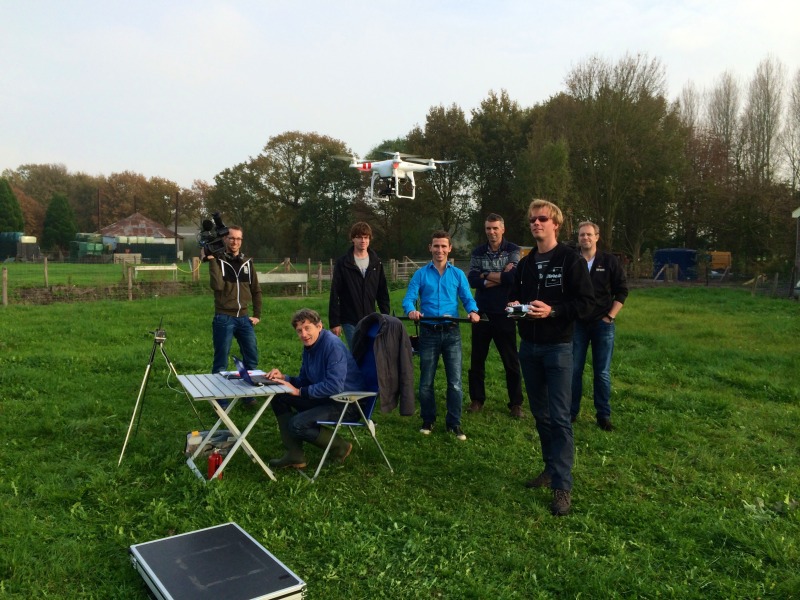

The next two weeks we went around the entire valley and visited our weather stations, snow observatories, soil moisture sensors, tipping buckets and the main glaciers in the valley. We were joined by other colleagues from ICIMOD for this part of the trip. We were pleasantly surprised and most stations were still functioning and we were able to collect gigabytes of real field data.

Throughout the trip it almost felt the pandemic did not exist and that taste of normality was more than welcome. I felt privileged to make the trip again and am looking forward to coming back in the years ahead with colleagues and students to try and understand and measure the changes in these beautiful high alpine regions. In the end, climate change will be a much bigger challenge we need to deal with than the current pandemic.